I used to think tea was about refreshment.

Back in California, I’d brew a bag in a mug, add a splash of oat milk, and call it self-care. Sometimes, I’d even light a candle, as if ambiance could compensate for haste. But in the Souss Valley, tea isn’t a pause between tasks. It’s the task itself. And it begins not with boiling water, but with waiting not the anxious kind, but the kind that opens you, like soil after rain.

I arrived in the valley late morning, dust still clinging to my clothes from the walk down from Taghazout. The ocean’s salt had dried on my skin, replaced now by the scent of olive trees, warm earth, and woodsmoke curling from courtyards hidden behind high walls. My throat was dry, my mind still humming with the rhythm of waves, but my body knew it needed to slow. I wasn’t looking for tea. I was just thirsty. But Amina saw me from her doorway the way locals always seem to see what you need before you ask and gestured for me to come in.

She didn’t offer a menu. Didn’t ask how I liked my tea. She simply filled a small pot with fresh mint from her garden, added green tea leaves, sugar cubes, and water drawn from a well that’s been feeding this village longer than anyone can remember. Then she placed it on the fire and sat beside me on a low bench beneath a fig tree.

“No rush,” she said in French, her voice soft as falling leaves. “The tea will tell us when it’s ready.”

The Morning Before Tea

Tea in the Souss Valley doesn’t begin when the water boils. It begins at dawn.

I learned this the next morning, when Amina invited me to walk with her to the communal oven the ferran where the women of the village gather to bake bread. We left before sunrise, the air still cool and damp, our sandals whispering against the packed earth path. She carried a large clay bowl covered with a cloth, inside which rested dough she’d kneaded the night before wheat from her cousin’s field, water from the well, salt from the market in Agadir, and time. Lots of time.

At the oven, already lit by an elder woman named Fatima, a circle of women worked in quiet rhythm. No one spoke loudly. No one hurried. Each had her turn, her place, her moment to slide her loaves into the glowing heat. The air was thick with the scent of baking bread and woodsmoke, and beneath it all, the low hum of shared presence.

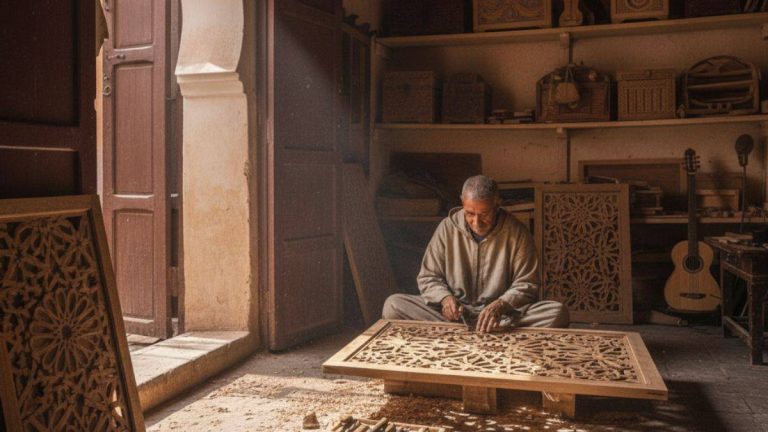

Amina didn’t explain what we were doing. She simply handed me a small broom made of palm fronds and nodded toward the floor. I swept. Not because I was expected to, but because it felt like the right thing to do part of the unspoken language of belonging. Later, as her bread baked, she plucked fresh mint from a patch near the oven wall, rinsing each sprig in a basin of cool water. “Tea starts here,” she said, holding up a glistening leaf. “Not with fire. With care.”

This is the first secret of the ritual: everything that comes before the pot matters. The bread must be warm. The mint must be washed by hand. The sugar must be broken with a stone, not crushed in a machine. These aren’t rules. They’re reminders that attention is the true ingredient, and haste is the only enemy.

The Three Pours of Patience

Back in Amina’s courtyard, the bread now cooling on a woven mat, she returned to the tea. The pot sat on a small brazier, its contents bubbling gently. She didn’t stir. Didn’t peek. Just watched the steam rise, her face calm, her hands resting in her lap.

“In the city,” she said, “people pour once and call it done. Here, we listen.”

Tea in the Souss Valley comes in three pours, each with its own character, its own purpose. The first is strong, almost bitter meant to wake the senses, to cut through distraction. The second is balanced, sweet and fragrant meant to open the heart, to invite conversation. The third is gentle, mellow, almost floral meant to settle the soul, to prepare you for what comes next.

She poured the first cup without ceremony. No fancy spout from a height. Just a steady hand, a quiet clink of glass on tray. “Drink slowly,” she said. “It’s not the tea you’re after. It’s the space it makes.”

I did. And as the warmth spread through my chest, something shifted. The urgency I’d carried from the coast the need to move, to plan, to document began to soften. Here, time wasn’t measured in minutes, but in the slow dissolve of sugar, the gradual darkening of the brew, the way sunlight moved across the courtyard wall.

This isn’t hospitality as performance. It’s presence as practice. No one here talks about “mindful tea.” They simply live it in the way they wash each mint sprig by hand, in how they listen to the sound of the water boiling to know when it’s hot enough, in the unhurried silence between pours.

If you’ve ever rushed through a meal just to get to the next thing if you sense that true connection might live not in efficiency, but in stillness then Where the Atlas Meets the Atlantic: Living Traditions Around Agadir reveals how this entire region, from coastal bays to mountain villages, offers a rhythm of return where waiting isn’t wasted time it’s the very ground of belonging.

Bread as Offering, Not Appetizer

While the tea steeped for the second pour, Amina brought out the bread still warm from the communal oven, its crust crackling faintly as she broke it. She didn’t serve it on a plate. She placed it directly on the cloth between us, tearing off a piece and handing it to me with both hands.

“In our house,” she said, “bread is never eaten alone. It’s shared before words, before news, before anything else.”

There were no olives, no cheese, no spreads. Just bread and tea. And yet, it felt like a feast. Because the meal wasn’t about flavor. It was about fellowship. Every tear of bread, every sip of tea, was a silent acknowledgment: We are here together. That is enough.

Later, I learned that this bread is baked only on certain days when the women gather at dawn, knead dough in large wooden troughs, and take turns tending the fire in the shared oven. It’s not convenience that dictates the schedule. It’s community. And the tea that follows isn’t dessert. It’s continuation a way to linger in the warmth of togetherness long after the hunger has passed.

One afternoon, I watched Amina’s neighbor, Leila, bring over a small loaf wrapped in cloth. No words were exchanged. Just a nod, a hand on the shoulder, the loaf placed gently on the windowsill. “She lost her brother last week,” Amina whispered later. “The bread says what words cannot.” In this valley, food isn’t just nourishment. It’s language. And tea is the silence that holds the conversation.

The Garden That Feeds the Pot

After the second pour, Amina rose and walked to the far corner of her courtyard, where a small garden thrived in the shade of a pomegranate tree. Rows of mint, thyme, and lemon verbena grew in neat patches, their leaves glistening with morning dew even at midday. She knelt, her fingers brushing the stems with the tenderness of someone who knows each plant by name.

“This mint,” she said, plucking a sprig, “is for guests. Strong, bright, full of sun.” She pointed to another patch, deeper green, growing near the wall. “That one is for family. Softer. For evenings, when the talk is quiet.”

She didn’t use pesticides. Didn’t measure yield. She simply tended, watered, and listened. “Plants speak,” she said, as if it were obvious. “You just have to be still enough to hear them.”

Back at the tray, she added a few leaves of the “family” mint to the pot for the third pour. The scent changed instantly less sharp, more rounded, like a sigh after a long day. This is another layer of the ritual: the tea isn’t standardized. It shifts with the season, the mood, the company. Some days, orange blossom is added. Others, a pinch of wild thyme. The recipe lives not in a book, but in the hands that prepare it.

And the water? Never from a tap. Always from the well, drawn in the cool hours before sunrise, when the air is still and the world feels new. “Cold water wakes the leaves,” Amina explained. “Hot water too soon burns them. You must let them meet gently.”

In a world that values speed and consistency, this kind of care feels radical. Not because it’s difficult, but because it refuses to be rushed, replicated, or commodified. It exists only in the moment it’s made and only for those willing to sit long enough to receive it.

The Silence Between Sips

The third pour arrived like a blessing gentle, amber-hued, carrying the quiet sweetness of orange blossom Amina had added without announcement. We sat in silence, sipping slowly, watching swallows dart above the rooftops, listening to the distant hum of a donkey cart on the road beyond the wall.

In California, I’d been taught that silence meant awkwardness a gap to be filled with words, music, or the buzz of a phone. But here, silence was the fabric of connection. It wasn’t empty. It was full of shared breath, of unspoken understanding, of the simple fact that two people could sit together without needing to prove anything.

Amina didn’t ask about my life. Didn’t offer advice. She just was. And in that being, she gave me permission to do the same. No performance. No storytelling. Just presence, as natural as the fig tree above us casting its shade.

Later, I learned this is how trust is built in the Souss Valley not through confessions, but through consistency. Showing up. Sharing bread. Waiting for the tea to be ready. The deepest conversations often happen not in words, but in the space between them in the way someone pours your cup without asking, or leaves a loaf on your windowsill when grief is too heavy to name.

This is the quiet strength of the ritual: it doesn’t demand your story. It simply holds space for you to exist within it.

From Courtyard Stillness to Mountain Stories

As the afternoon deepened, the light turned golden, and the last drops of tea cooled in our glasses. Amina rose slowly, gathered the tray, and nodded toward the hills rising in the distance where the Anti-Atlas begins its slow climb into the sky. “Up there,” she said, “they tell stories under fig trees. Not to entertain. To heal.”

In this part of Morocco, the valley doesn’t end at the fields. It flows upward, into stone villages perched on ridges, where time moves even slower and silence carries more weight. The same patience that teaches you to wait for the third pour of tea also prepares you to sit beneath a fig tree in those high villages, where elders speak in parables, children listen without interrupting, and wounds are tended not with advice, but with witness.

You don’t leave the valley abruptly. You carry its stillness with you in the way you breathe, in how you listen, in your willingness to let a conversation unfold without steering it toward a point. The tea ritual isn’t confined to the courtyard. It’s a way of moving through the world: attentive, unhurried, open.

And if your spirit has been calmed by the rhythm of three pours and shared bread if you’ve learned that healing often arrives in silence, not speech then Under the Fig Tree: Stories That Mend in the Anti-Atlas Villages will guide you to the shaded courtyards where memory is medicine, and where every story told is a thread woven back into the fabric of belonging.

Waiting as Resistance

Now, back in Los Angeles, when I feel the pressure to respond instantly to emails, messages, expectations I sometimes stop. I fill a pot with water. I wash mint under cool running tap. I break sugar cubes with the back of a spoon. And I wait.

Not because I need tea. But because I need to remember that some things cannot be rushed. That presence is not passive it’s an act of quiet rebellion against a world that treats slowness as failure and stillness as waste.

Amina never called it wellness. She just called it living. And in a culture that equates speed with success, choosing to sit, to share bread, to wait for the third pour that’s not indulgence. It’s resistance. It’s saying: I will not let urgency steal my humanity.

Sometimes, on Sunday mornings, I invite a friend over. No agenda. No topic. Just bread from the local bakery (never quite the same, but close enough), mint from my windowsill pot, and a small pot on the stove. We pour three times. We sit. We let the silence do its work.

And in those moments, I’m back in Amina’s courtyard, beneath the fig tree, learning that the most profound traditions aren’t shouted. They’re whispered in steam rising from a simple pot, in the crackle of fresh bread, in the art of waiting together.

The Well That Never Runs Dry

Before I left the valley, Amina walked me to the edge of her land, where a stone well stood beneath an old olive tree. Its wooden pulley was worn smooth by generations of hands, its rope frayed but strong. She drew a bucket, the water clear and cold, and offered me a drink.

“This is where it all begins,” she said, watching the ripples settle. “Not with tea. Not with bread. With water that remembers every hand that’s touched it.”

I drank. The water was crisp, alive, tasting of earth and time. In that moment, I understood: the ritual isn’t about the ingredients. It’s about the lineage. Every pour carries the patience of mothers who waited before you. Every loaf holds the warmth of ovens lit for centuries. Every silence echoes with the presence of those who knew that to be together, truly together, is the deepest form of care.

You can’t replicate this in a café. You can’t package it for export. It only lives here the rhythm of the valley, in the hands that tend the mint, in the hearts that choose to wait.

And as I walked back toward the road, the taste of mint still on my tongue, the weight of shared bread in my memory, I carried something far more valuable than a recipe. I carried the quiet certainty that wellness isn’t something you chase. It’s something you return to again and again like water drawn from a well that never runs dry.