I didn’t expect to find healing in sound.

In California, I’d chased silence retreats in the redwoods, noise-canceling headphones, apps that promised “deep calm.” But in Dakhla, it was the opposite: healing came not from the absence of noise, but from its rhythm. Specifically, from the deep, resonant pulse of the tbal a goatskin drum played not for performance, but for presence.

I first heard it at dusk, walking past a courtyard near the old port. The air was still warm from the day, scented with salt and woodsmoke. No stage, no audience, just three men seated in a circle on low mats, one with a drum between his knees, another humming a low melody, the third swaying gently, eyes closed. They weren’t playing for anyone. They were playing with something something older than words, deeper than song, woven into the very fabric of wind and wave.

When I paused at the edge of the courtyard, an elder motioned me to sit without breaking rhythm. He didn’t speak. He just poured tea from a small pot and nodded toward the drum. “Listen,” he said, his voice barely above the beat. “Not with your ears. With your bones.

The Drum as Medicine

His name was Brahim, and he’d been playing the tbal since he was a boy of seven, taught by his grandfather who learned from his own father before him. “My grandfather said the drum doesn’t make music,” he told me later, running his calloused fingers over the stretched skin. “It releases what’s stuck. Grief, fear, even joy if it sits too long, it hardens. The drum softens it.”

In Dakhla, music isn’t entertainment. It’s medicine. And the tbal is its most trusted healer not because of its sound, but because of its silence between beats. “That’s where the healing lives,” Brahim explained. “In the space between. Not in the noise, but in what the noise makes room for.”

He showed me how the tension of the skin is adjusted with heat held briefly over coals, never boiled so it responds to the lightest touch. “A stiff drum shouts,” he said. “A wise one whispers.”

One evening, I watched him play for a young fisherman who’d lost his brother at sea during a sudden squall. No lyrics. No chorus. Just a slow, steady beat that mimicked the pull of the tide retreating and returning. The young man sat cross-legged, hands on his knees, eyes closed. After ten minutes, his shoulders began to shake. Then tears came not from sadness, but from release, as if the rhythm had untied a knot deep inside. “The drum remembered his brother’s name,” Brahim said afterward, wiping his brow. “Even when his tongue couldn’t say it.”

This isn’t therapy as we know it. There’s no couch, no diagnosis, no hourly rate. Just skin, wood, breath, and the courage to let rhythm move through you until your body remembers how to breathe again.

For those who’ve felt that true healing begins not with talking, but with trembling, Dakhla’s Pulse: Traditions Where the Sahara Greets the Atlantic reveals how an entire region uses sound, silence, and shared breath to mend what words cannot touch.

Rhythm That Rises with the Tide

What struck me most wasn’t the drum alone, but how it listened to the sea.

Brahim never played the same rhythm twice in a row. “The tide changes,” he said, adjusting the strap around his shoulder. “So must the beat.” On calm mornings, his strokes were light, almost playful like ripples over wet sand. After a storm, they grew deeper, slower, resonant with the weight of waves crashing against the cliffs. And during the sardine runs, when the bay shimmered with silver schools moving as one body, his hands moved fast, joyful, echoing the pulse of abundance.

He taught me to hear the connection: the crash of waves, the sigh of wind through dunes, the low hum of boats returning at dawn all of it part of one great rhythm. “The drum doesn’t lead,” he said. “It follows. It listens. You don’t command the sea. You learn its language.”

One afternoon, I sat with him on the shore as he tapped a quiet pattern on the edge of his drum just fingertips, no palm. No song. Just a heartbeat. “This is for waiting,” he said. “For when you don’t know what comes next, or if anything will come at all.” I closed my eyes and felt it not just in my ears, but in my chest, my feet, the soles pressed into cool sand. The anxiety that had clung to me since Los Angeles the constant hum of deadlines, notifications, expectations began to loosen, not because I’d solved anything, but because I’d been reminded: I was part of something larger. A rhythm that didn’t need me to be perfect only present.

In Dakhla, wellness isn’t about fixing yourself. It’s about rejoining the flow. And the drum is the bridge.

Voices That Carry Without Words

Not all healing in Dakhla comes from drums. Sometimes, it rises from the throat in chants called madih, sung not to praise, but to release. I heard my first madih at a gathering after a long drought that had dried wells and thinned herds. No instruments. Just men and women seated in a circle under a tamarisk tree, voices rising in unison, low and resonant, like wind through a canyon. The words were in Hassani Arabic, but I didn’t need translation. The sound itself carried meaning: longing, gratitude, resilience.

An elder named Fatima, her face lined like desert maps, explained that these songs aren’t memorized. They’re received. “When the heart is full, the voice finds its path,” she said, stirring a pot of mint tea. “You don’t sing to be heard. You sing so the weight can leave your chest. Like exhaling a stone.”

Later, I watched her lead a group of women who’d lost homes in a rare flood that swept through the outskirts of town. They didn’t speak of their loss. They sang. And as their voices wove together some high like seabirds, some deep like dunes, some trembling like reeds the air itself seemed to soften. One woman began to sway, arms loose at her sides. Another wept silently, tears tracing paths through the dust on her cheeks. No one interrupted. No one offered advice. The song held them all, like a net catching what would otherwise fall.

This is the quiet power of Dakhla’s sound traditions: they don’t demand you articulate your pain. They give it space to move. And in that movement, it transforms not into something pretty, but into something bearable, something shared.

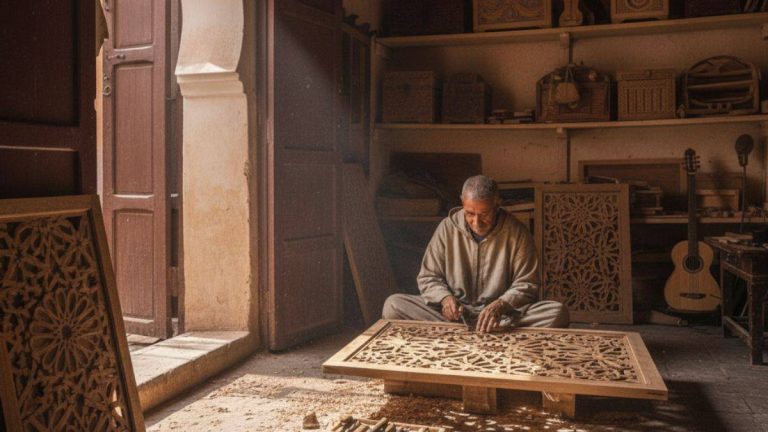

The Circle That Holds Sound

There are no stages in Dakhla’s musical traditions. Only circles.

And in those circles, hierarchy dissolves. The drummer isn’t a performer. The singer isn’t a star. Everyone is both listener and vessel. I joined one such circle on a moonless night, seated on woven mats in a courtyard open to the stars, the Atlantic a distant murmur beyond the dunes. Brahim began with a single beat. Then Fatima added a hum, low and steady. A young boy, no older than ten, tapped his fingers on a clay pot left over from dinner. An old fisherman, his hands gnarled from decades of net work, clapped softly, in time with his breath.

No one led. No one followed. The sound simply rose like heat from the sand, like mist from the sea, like breath from sleeping children. It wasn’t music you consumed. It was music you entered.

“What you hear isn’t ours,” Brahim told me afterward, handing me a date. “It belongs to the wind, the waves, the ancestors. We just make space for it to pass through. Like a doorway.”

This is the opposite of performance. It’s participation. And in that participation, something shifts: the self softens. You stop being the one who needs healing, and become part of the healing itself. Your breath joins the rhythm. Your silence becomes part of the song. Your presence matters not for what you say, but for the space you hold.

In a world that turns music into content streamed, liked, consumed, discarded this feels like rebellion. Not loud. Not angry. Just deeply, quietly human.

If your spirit has been worn thin by noise that demands attention but offers no nourishment, The Shore That Walks With You will carry you to Dakhla’s empty beaches, where silence isn’t absence, but presence and where walking alone becomes a conversation with the infinite.

When the Drum Remembers You

On my last night in Dakhla, Brahim invited me to sit with him one final time. No circle. No audience. Just the two of us on the roof of his house, the Atlantic whispering below, the stars thick overhead like scattered salt. He didn’t speak. He simply placed the tbal in my lap and nodded.

I hesitated. “I don’t know how,” I said, my palms suddenly damp.

“You don’t need to,” he replied, his eyes reflecting starlight. “Just let your hands remember what your mind has forgotten. The rhythm is already in you. It’s in your walk, your breath, your blood.”

So I touched the skin. And without thinking, my fingers began to move slow at first, tentative, then steadier, finding a rhythm that felt like breath, like tide, like home. I wasn’t playing for anything. I was playing with something ancient, something that had been waiting in my bones all along, buried under years of schedules and screens.

Tears came not from sadness, but from recognition. In that moment, I wasn’t a writer, a traveler, a man from California chasing calm. I was just a body remembering how to be alive in time, in space, in sound.

Brahim smiled. “The drum knew you,” he said. “It always does.”

Back in Los Angeles, I don’t have a tbal. But sometimes, when the noise of the city grows too loud the sirens, the horns, the endless ping of messages I close my eyes and tap my fingers on my desk once, twice, three times until I find the rhythm again. Not to escape. But to return.

Because healing in Dakhla isn’t about leaving your life behind.

It’s about remembering how to move through it with your whole self, in time, in trust, in tide.