I didn’t go to Fes looking for paper.

I went because I’d lost my words not just the ability to write them, but the trust that they mattered.

In California, I’d written myself into exhaustion chasing deadlines, optimizing headlines, turning stories into metrics, and my own voice into a product to be packaged and sold. My notebooks were full of half-finished thoughts, my hard drive cluttered with drafts that never felt complete. I was producing, but not creating. Speaking, but not saying anything true. So when a friend who’d studied calligraphy in Morocco said, “Go to Fes. Not to write. Just to be near paper that remembers how to breathe,” I packed a single bag, left my laptop behind, and boarded a flight with nothing but a blank journal I knew I wouldn’t open.

What I found wasn’t a craft. It was a rhythm. And it began not with ink, but with silence with hands stirring vats of water and linen under a sky so blue it felt like memory made visible.

The Vat That Holds Time

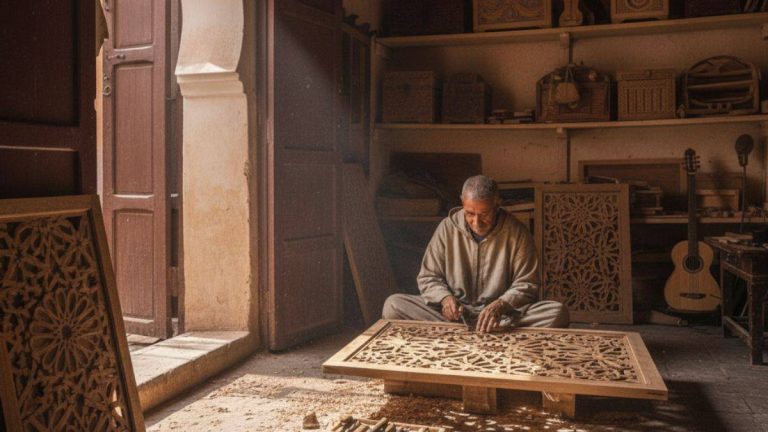

The papermakers of Fes don’t work in studios with glass walls and Instagrammable lighting. They work in hidden courtyards tucked behind unmarked doors in the medina, where the only sign of their presence is the soft sound of water dripping from wooden frames and the faint, clean scent of wet linen hanging in the air like a secret.

I met Youssef in one such courtyard, his arms stained with the pale gray of pulp, his hands moving slowly through a vat of water as if combing the breath of the earth itself. He didn’t greet me with a tour or a price list. He simply handed me a small glass of mint tea and pointed to a low stone bench beneath a fig tree. “Sit,” he said. “The paper isn’t ready yet. Neither are you.”

For three hours, I watched him work. No machines. No electricity. Just a stone basin worn smooth by centuries of use, a wooden frame strung with fine mesh, and sheets of linen soaked for weeks until they softened into fiber. He stirred the mixture with a long paddle carved from olive wood, its handle darkened by generations of hands. Then he dipped the frame, lifted it slowly, and let the water drain through the mesh, leaving behind a thin, trembling layer of pulp. “This,” he said, holding it up to the light, “is where time begins not when you write, but when you wait.”

Later, I learned that each sheet takes three full days to make not because the process is slow, but because it must wait. The linen must soak until it forgets it was cloth. The pulp must settle until it finds its own balance. The sheet must dry in the shade, never in direct sun, or it will crack from the haste. “Paper isn’t made,” Youssef explained, wiping his brow with the back of his hand. “It’s allowed to become. Like a child. Like a story. Like grief.”

In a world that demands instant output, this felt like rebellion. Not loud. Not angry. Just deeply, stubbornly human.

For those who’ve felt that true creation begins not with pressure, but with patience, Fes Unfolds: Traditions Where Time Stacks in Layers reveals how an entire city heals not by producing more, but by preparing deeply and how some of the most important things in life, like paper, like stories, like souls, cannot be rushed.

The Hand That Learns to Wait

Youssef didn’t let me touch the pulp on my first day. “Your hands are too fast,” he said, watching me fidget with my empty notebook, my fingers twitching as if searching for a keyboard that wasn’t there. “They still think in clicks. In deletes. In likes. Here, we think in breaths.”

Instead, he gave me a task: sit by the drying racks and watch the sheets change color as they dried pale gray at dawn, soft white by noon, warm ivory by dusk. “Don’t count them,” he warned. “Don’t plan what you’ll write on them. Just see how they breathe. How they hold the light. How they become.”

So I sat. And for the first time in years, I did nothing but observe. No phone. No notes. No internal monologue about what this “meant” or how I could “use” it for content. Just presence. And slowly, something shifted. My shoulders dropped. My breath deepened. The urgency that had lived in my chest like a second heartbeat the constant hum of “what’s next?” began to quiet, not because I silenced it, but because the space around me held it gently, like water holds a stone.

On the third day, he handed me a wooden frame identical to his own. “Now,” he said, “your hands are ready.”

I dipped it into the vat, lifted it slowly, and watched the water drain through the mesh. It was harder than it looked. Too fast, and the sheet tore at the edges. Too slow, and it thickened unevenly, heavy in the center. But Youssef didn’t correct me. He didn’t say “wrong.” He just nodded and said, “Again.”

By the tenth try, my movements slowed. Not because I was trying to be slow, but because my body had finally remembered how to listen to the weight of the water, the tension of the mesh, the silence between actions.

In Fes, learning isn’t about mastery. It’s about surrender. And the paper teaches you that not everything needs to be held tightly to be held well. Sometimes, the gentlest touch leaves the deepest mark.

The Ink That Follows the Breath

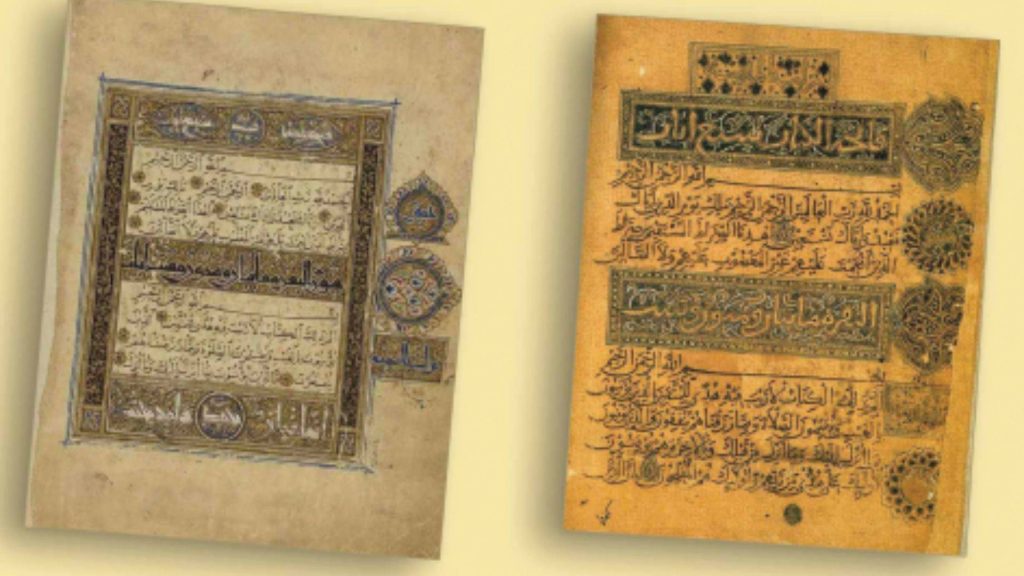

Paper in Fes is never meant to be blank for long. But the ink that meets it isn’t bought in bottles from a store. It’s made by hand, from soot collected from oil lamps, gum arabic tapped from acacia trees in the Atlas foothills, and rainwater gathered in clay jars on rooftops during the rare winter storms.

I watched an old calligrapher named Lalla Amina grind charcoal with a stone pestle in her courtyard, her movements slow, rhythmic, almost meditative. She didn’t speak at first. She just worked, her hands steady, her eyes focused on the texture forming under the stone. After a while, she said without looking up, “Ink isn’t poured. It’s invited. If you rush it, it flees. If you respect it, it stays.”

She showed me how to mix it: three parts soot, two parts gum, one part water and patience. “If you rush the gum, it clumps like fear. If you stir too hard, the soot escapes like a startled bird. You must move like your breath steady, calm, unhurried.”

When the ink was ready, thick and black as midnight, she dipped a reed pen she’d cut herself and wrote a single word on the sheet Youssef had made: Sabr patience. The ink didn’t sit on the surface. It sank in, as if the paper had been waiting for it all along, as if the fibers opened to receive it like a long-lost friend.

Later, I learned that students of calligraphy in Fes spend months sometimes years writing just this one word over and over, not to perfect the shape, but to embody its meaning in their hands, their posture, their breath. “Your hand must learn what your mind already knows,” Lalla Amina said, handing me the pen. “That some things cannot be forced. They can only be welcomed.”

In a world that rewards speed, volume, and visibility, this felt like sanctuary. Not escape. But return to a rhythm where creation isn’t extraction, but conversation between hand, material, and time.

If your spirit has been stirred by the quiet discipline of ink and fiber if you sense that true expression lives not in how much you say, but in how deeply you mean it then The Scent That Guides the Lost will carry you deeper into Fes’ hidden courtyards, where fragrance, not maps, leads the way through memory, healing, and the art of being found.

The Sheet That Remembers You

On my last morning in Fes, Youssef handed me a single sheet of paper ivory-white, slightly rough to the touch, still carrying the faint, clean scent of linen and rain. “This one,” he said, his eyes crinkling at the corners, “was made while you were here. Your silence helped it dry.”

I ran my fingers over its surface. It felt alive not smooth and sterile like printer paper, but textured, breathing, full of tiny imperfections that gave it character, history, soul. He didn’t offer it for sale. He didn’t suggest I write a masterpiece on it. He simply said, “Keep it. Not to use. To remember that you, too, are allowed to wait.”

Back in Los Angeles, I placed it on my desk, untouched. No notes. No drafts. Just presence. And whenever I feel the old urgency rising the need to produce, to publish, to prove I’m still relevant I touch its surface. Instantly, I’m back in that courtyard: the sound of water dripping from the frames, the warmth of sun on ancient stone, the quiet certainty that some things are made not to be filled, but to be held.

In Fes, paper isn’t a blank slate waiting for meaning to be imposed upon it. It’s a witness. It holds the memory of hands that stirred, waited, and let go. And in that holding, it teaches us that we, too, don’t need to be filled with achievements to be whole. We only need to be present.

Because healing doesn’t always come from writing your story.

Sometimes, it comes from learning to sit with the silence before the first word and trusting that the page will wait for you, just as you are.