I didn’t go to Fes looking for color.

I went because I’d lost my sense of depth not just in vision, but in feeling. In California, my world had flattened into screens: pixels of curated perfection, filters that smoothed every edge, feeds that blurred joy and sorrow into the same pastel tone until I couldn’t tell one emotion from another. I could name every shade of beige in a high-end design catalog, but I couldn’t tell you how grief sat in my chest or how joy warmed my palms. My eyes had grown tired of surfaces that promised everything but held nothing. So when a friend who’d apprenticed with natural dyers in Morocco said, “Go to Fes. Not to see color. Just to feel it,” I left my camera behind, turned off my phone, and walked into the souks with nothing but open eyes and a hunger for truth that couldn’t be filtered.

What I found wasn’t pigment. It was prayer made visible in steam, roots, minerals, and hands that knew how to wait for the earth to speak not in words, but in hue.

The Vat That Holds the Earth’s Breath

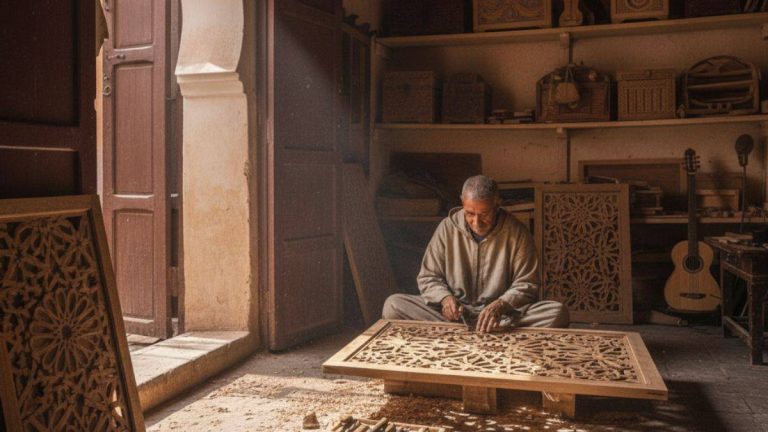

The dyers of Fes don’t work in studios with labeled bottles, pH meters, or Instagrammable backdrops. They work in narrow alleys near the Oued Fes, where stone vats some worn smooth by centuries of use sit over low fires fueled by olive wood, filled with water, plants, and time. The air smells of woodsmoke, wet wool, and something deeper: the scent of transformation, like rain on dry earth after a long drought.

I met Youssef in one such alley, his arms stained with indigo, saffron, and henna, his hands moving slowly through a vat of simmering liquid as if combing the breath of the earth itself. He didn’t greet me with a price list or a demonstration. He simply handed me a small glass of mint tea and pointed to a low stone bench beneath a fig tree. “Watch,” he said. “The color isn’t added. It’s released. Like a secret the earth has been holding.”

For hours, I watched him work. No machines. No synthetic chemicals. Just roots dug by hand from the Atlas foothills, leaves gathered after the first spring rain, minerals scraped from desert cliffs near Erfoud all steeped in rainwater collected in winter and stored in clay jars, left to ferment for days, sometimes weeks, until the liquid turned deep, alive, breathing. He stirred the mixture with a long wooden paddle carved from olive wood, its handle darkened by generations of hands. Then he dipped skeins of raw, undyed wool, lifting them slowly, letting the excess drip back into the vat like an offering returned to the source.

“This,” he said, holding up a strand now glowing with the red of crushed cochineal beetles harvested from prickly pear cacti, “isn’t dye. It’s memory. The earth remembers the sun that ripened the fruit, the rain that softened the soil, the hand that gathered it with care. And if you’re quiet, it will tell you its story not in words, but in warmth, in depth, in truth.”

For those who’ve felt that true color isn’t seen, but felt in the bones, Fes Unfolds:Traditions Where Time Stacks in Layers reveals how an entire city heals not by brightening surfaces, but by deepening presence through roots, steam, and the slow alchemy of patience that turns matter into meaning.

The Hand That Waits for the Earth

Youssef didn’t let me touch the wool on my first day. “Your hands are too fast,” he said, watching me reach toward a skein of undyed yarn, my fingers twitching as if searching for a screen to scroll. “They still think in downloads, in likes, in instant results. Here, we think in seasons. In waiting. In trust.”

Instead, he gave me a task: sit by the drying racks and watch the colors change as they oxidized pale yellow at dawn deepening to gold by noon, soft blue at sunrise ripening into indigo by dusk, madder root shifting from pink to rust as the sun moved across the sky. “Don’t name them,” he warned. “Don’t compare them to Pantone codes or phone screens. Just see how they breathe. How they hold light. How they become not all at once, but slowly, honestly.”

So I sat. And for the first time in years, I did nothing but observe. No phone. No notes. No internal monologue about what this “meant” or how I could “use” it for content. Just presence. And slowly, something shifted. My eyes softened. My breath deepened. The flatness that had lived in my vision like a film began to lift not because the world changed, but because I finally stopped trying to frame it, crop it, or sell it.

On the third day, he handed me a small skein of raw wool, still smelling of sheep and mountain air. “Now,” he said, “your hands are ready to listen.”

I dipped it into a vat of henna, lifted it slowly, and watched the liquid drain. It was harder than it looked. Too fast, and the color bled unevenly, streaked and shallow. Too slow, and it darkened beyond recognition, losing its luminosity. But Youssef didn’t correct me. He didn’t say “wrong.” He just nodded and said, “Again.”

By the tenth try, my movements slowed. Not because I was trying to be slow, but because my body had finally remembered how to listen to the weight of the wool, the temperature of the dye, the silence between actions. On the fifteenth dip, the color settled evenly, warm and alive. “Good,” he said. “Not perfect. But honest.”

In Fes, learning isn’t about control. It’s about surrender. And the dye teaches you that not everything needs to be forced to be beautiful. Sometimes, the deepest red comes not from pressure, but from patience.

The Steam That Carries Memory

Not all color in Fes comes from plants. Some rises from stone, fire, memory, and the quiet chemistry of air and time.

I met Fatima in a shaded courtyard behind the dyers’ alley, where she tended vats of indigo a dye so ancient it’s said to have been used by Phoenician sailors and Berber queens alike. Her hands were stained blue up to the elbows, her apron darkened by decades of work, her eyes sharp with the focus of those who know their craft is sacred. “Indigo doesn’t live in the plant,” she told me as she stirred a vat that smelled of earth, iron, and something faintly sweet, like fermentation. “It lives in the air. In the waiting. In the breath between dips.”

She showed me how the process works: raw wool is dipped into the vat, pulled out green, then left to hang in the sun. As it meets the air, it oxidizes slowly, magically turning from green to blue, then deepening into a shade so rich it feels like midnight given form, like the sky just before stars appear. “You can’t rush it,” she said, her voice steady as the steam rising from the vat. “If you dip too soon, the color fades like a forgotten promise. If you wait too long, it cracks like a heart that’s held too much. You must listen to the steam. It tells you when it’s ready.”

I stayed through the afternoon. As the sun shifted, the drying racks filled with skeins in every stage of transformation pale sky, ocean depth, stormy violet, midnight black. Each one carried the story of its making: the hand that gathered the leaves at dawn, the fire that heated the water with olive wood, the patience that held the space between dips, the silence that honored the process.

Later, I watched her give a skein of deep indigo to an old woman who’d lost her husband two winters ago. No words passed between them. Just the wool, pressed into her palm. The woman closed her eyes, ran her fingers over the fibers, and wept not from sadness, but from recognition. The color had brought back his djellaba, the way it shimmered in the market light, the smell of woodsmoke and cedar clinging to its folds, the way he’d wrap it around his shoulders on cold mornings. In that moment, grief wasn’t erased. It was honored in thread, in time, in trust.

In Fes, dye isn’t decoration. It’s devotion. And those who work with it aren’t artisans. They’re keepers of memory, alchemists of belonging, priests of patience.

If your spirit has been shaped by screens until it forgets the weight of true color if you’ve sensed that healing sometimes arrives not in words, but in a single thread that carries the memory of love, loss, and return then No Maps in the Medina of Fes will carry you deeper into the labyrinth, where getting lost becomes the clearest path home.

The Thread That Remembers You

On my last morning in Fes, Youssef handed me a small skein of wool dyed in saffron gathered from the hills outside Taliouine, its color warm as sunrise over desert dunes, rich as honey, deep as gratitude. “This one,” he said, his eyes crinkling at the corners like old parchment, “was dyed while you were here. Your silence helped it steep. Your presence gave it depth.”

I ran my fingers over the fibers. They felt alive not smooth and sterile like synthetic thread, but textured, breathing, full of tiny imperfections that gave it character, history, soul. He didn’t offer it for sale. He didn’t suggest I weave it into a scarf or frame it as art. He simply said, “Keep it. Not to use. To remember that you, too, are allowed to steep to wait in the dark, to change slowly, to become without announcement.”

Back in Los Angeles, I keep it on my desk, wrapped in a scrap of undyed cotton, next to a sprig of dried rosemary. No frame. No display. Just presence. And whenever the world feels flat again when screens blur my vision, feeds flatten my feeling, and I start believing that everything must be bright, fast, and loud I hold it in my hands. Instantly, I’m back in that alley: the scent of woodsmoke and wet wool, the sound of water bubbling in stone vats, the warmth of sun on ancient walls, the quiet certainty that some things are made not to be seen, but to be felt.

In Fes, color isn’t just hue. It’s witness. It remembers who you were when you arrived hurried, shallow, fragmented and who you became when you left: deeper, slower, whole. And it waits not to bring you back, but to remind you that you never truly left yourself behind.

Because healing doesn’t always come from brightening the surface.

Sometimes, it comes from learning to steep in the dark and trust that even the deepest indigo began as green.