I didn’t go to Fes looking for a city.

I went because I’d forgotten how to be human not broken, not lost, but simply out of rhythm with the quiet pulse that moves beneath the noise of modern life. In California, I’d mastered the art of doing: writing on deadline, optimizing headlines for clicks, moving through days like a checklist of outputs. My calendar was color-coded, my inbox empty by noon, my productivity metrics glowing green. But inside, I was hollow. My hands moved constantly typing, swiping, grabbing coffee but they hadn’t felt anything real in years. My eyes scanned screens, but they no longer saw depth. My breath was shallow, hurried, always racing toward the next task. I was efficient, visible, and utterly disconnected from the slow, steady rhythm that once made me feel alive.

So when a friend who’d spent a decade restoring riads in Morocco said, “Go to Fes. Not to see. Just to let it unfold you,” I left my phone in airplane mode, turned off my watch, and walked into the medina with nothing but open hands and the quiet hope that if I stopped trying to produce meaning, meaning might finally find me not as a product, but as a presence.

What I found wasn’t a destination. It was a living library of slowness a city where time doesn’t pass, but stacks; where healing isn’t extracted, but allowed to rise like steam from a vat of indigo, breath from a potter’s wheel, or scent from dried rose petals. Fes doesn’t offer wellness as a service. It offers it as an invitation to surrender, to wait, to trust that some things cannot be rushed, only received. And in that surrender, six paths unfolded each one a tradition, each one a mirror, each one a way back to the body, the breath, the self.

The Paper That Waits for the Hand in Fes

In a world that demands instant output, Fes’ papermakers practice radical patience. They don’t work in studios with glass walls and Instagrammable lighting. They work in hidden courtyards tucked behind unmarked doors in the medina, where the only sounds are the soft drip of water from wooden frames and the faint, clean scent of wet linen hanging in the air like a secret carried on the wind. The courtyards are cool even in summer, shaded by fig trees whose roots have cracked the ancient stone floors over centuries. There are no signs, no price lists, no demonstrations for tourists. Just presence.

I met Youssef in one such courtyard, his arms stained with the pale gray of pulp, his hands moving slowly through a vat of water as if combing the breath of the earth itself. He didn’t greet me with a tour. He simply handed me a small glass of mint tea and pointed to a low stone bench beneath a fig tree. “Sit,” he said. “The paper isn’t ready yet. Neither are you.”

For three hours, I watched him work. No machines. No electricity. Just a stone basin worn smooth by centuries of use, a wooden frame strung with fine mesh, and sheets of linen soaked for weeks until they softened into fiber. He stirred the mixture with a long paddle carved from olive wood, its handle darkened by generations of hands. Then he dipped the frame, lifted it slowly, and let the water drain through the mesh, leaving behind a thin, trembling layer of pulp. “This,” he said, holding it up to the light, “is where time begins not when you write, but when you wait.”

Later, I learned that each sheet takes three full days to make not because the process is slow, but because it must wait. The linen must soak until it forgets it was cloth. The pulp must settle until it finds its own balance. The sheet must dry in the shade, never in direct sun, or it will crack from the haste. “Paper isn’t made,” Youssef explained, wiping his brow with the back of his hand. “It’s allowed to become. Like a child. Like a story. Like grief.”

In a world that rewards speed, volume, and visibility, this felt like sanctuary. Not escape. But return to a rhythm where creation isn’t extraction, but conversation between hand, material, and time. For those who’ve written themselves into exhaustion, who’ve turned their voice into a product to be packaged and sold, this tradition offers a different path one where healing comes not from writing your story, but from learning to sit with the silence before the first word. If your hands have grown tired of producing, The Paper That Waits for the Hand in Fes will carry you to courtyards where pulp becomes prayer, and waiting becomes the deepest form of creation.

The Scent That Guides the Lost Through Fes’ Medina

Fes doesn’t guide you with signs. It guides you with scent. In the medina, there are no maps, no GPS coordinates, no numbered alleys. Instead, there’s rosewater for grief that sits in the chest like stone, cedar for fear that tightens the throat, and orange blossom for exhaustion that lives in the bones. The medina swallows you whole one moment you’re on a wide street with taxis honking; the next, you’re in a narrow passage barely wide enough for two shoulders, where sunlight filters through cracks in wooden lattices, donkeys carry sacks of olives balanced like prayers, and voices echo in Tamazight, Arabic, and French all at once, yet never in conflict.

I wandered for hours, turning corners at random, trusting nothing but my feet and the faint hum of my own pulse. Then, near a bend shaded by ancient fig trees, I caught it: a warm, resinous aroma that pulled me toward an unmarked doorway draped with faded indigo cloth. Inside, an old woman named Lalla Khadija sat behind a low table covered in small clay bowls each filled with a different powder, oil, or dried herb. She didn’t speak. She just held out a sprig of dried rosemary. “Breathe,” she said, her voice soft as falling dust.

She explained that each blend serves not to perfume, but to restore balance. “You don’t choose the scent,” she said, stirring a mixture of crushed mint and sea salt. “It chooses you. By how your breath changes when you smell it. If your shoulders drop, it’s speaking to your body. If your eyes water, it’s speaking to your soul.” She offered “breath tests” placing bowls of rose, cedar, and amber before me. With the rose, my chest tightened old grief resurfaced. With the cedar, my shoulders dropped as if a weight I hadn’t named was finally seen. “That one,” she said, “is yours today.”

She mixed it with argan oil and sea salt, then dabbed it on my wrists and chest. “This isn’t fragrance,” she said. “It’s memory. Cedar remembers mountains. Salt remembers ocean. Together, they remind you that you are held even when you feel lost.”

In Fes, healing doesn’t come from escaping the labyrinth. It comes from learning to listen to its whispers and trusting that the right scent will always find you when you’re ready to be found. For those who’ve felt that true guidance comes not from maps, but from presence, The Scent That Guides the Lost Through Fes’ Medina reveals how fragrance, not landmarks, becomes the true compass through memory, healing, and the art of being found.

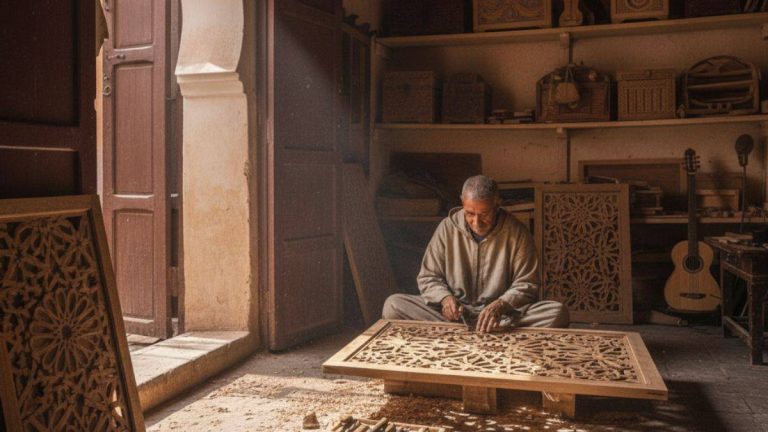

Hands That Shape Silence in Fes’ Clay

In Fes, silence isn’t absence. It’s shaped into form. The potters don’t work with machines or electricity. They work in sunlit courtyards off narrow alleys near the Chouara Tannery, where the only sounds are the soft slap of wet clay, the creak of an old wooden wheel turned by foot, and the distant call to prayer echoing off ancient walls. The clay comes from a red-earth quarry near the Oued Fes, dug by hand, aged for months in shaded pits, and mixed with rainwater collected in winter.

I met Hassan in one such courtyard, his hands coated in red clay, his feet moving slowly on the pedal that spun the wheel. He didn’t greet me with a price list. He simply pointed to a low stool and handed me a lump of raw earth. “Feel it,” he said. “Don’t think. Just feel.”

For an hour, I sat and watched him work. No music. No phone. Just hands coaxing shape from mud, fingers reading the clay like braille. When the vessel began to rise thin, smooth, breathing he slowed his foot, let the wheel spin freely, and placed his palms gently around the rim. “This,” he whispered, “is where silence lives not in the absence of sound, but in the presence of attention.”

Hassan didn’t let me touch the wheel on my first day. “Your hands are too loud,” he said. Instead, he gave me a task: sit by the drying racks and watch the vessels change as they hardened wet and dark at dawn, firm and pale by noon, cool and resonant by dusk. “Don’t count them,” he warned. “Just see how they hold space.”

On the third day, he handed me a small mound of prepared clay. I placed it on the wheel, pressed the pedal, and tried to center it. It wobbled. Collapsed. Spun off. But Hassan didn’t correct me. He just said, “Again.” By the tenth try, my movements slowed. Not because I was trying to be slow, but because my body had finally remembered how to listen to the weight of the clay, the spin of the wheel, the silence between actions.

Behind the courtyard stood a low, dome-shaped kiln built from the same red earth as the clay it fired. Every week, Hassan loads it with dozens of vessels bowls, plates, tagines each one shaped by hand, dried in the shade, and left to rest for days before facing the flame. “Fire doesn’t punish,” he told me as he stacked greenware inside. “It reveals. What was weak cracks. What was honest becomes strong.”

Broken pieces aren’t discarded. They’re ground into powder and mixed back into new clay a practice called khammash. “Nothing is wasted,” Hassan explained. “Even failure becomes part of the next vessel.”

In a world that demands perfection, Fes teaches that resilience isn’t about never breaking. It’s about knowing how to return to the earth and rise again. For those whose hands have grown loud with typing and swiping, Hands That Shape Silence in Fes’ Clay offers a return to touch, to texture, to the quiet courage of being unfinished.

The Courtyard That Holds a Thousand Whispers of Fes

Fes’ riads aren’t just houses. They’re vessels of presence. Built around central courtyards open to the sky, they are designed not for beauty alone, but for balance. The height of the walls, the angle of the roof opening, the placement of the fountain all crafted to harmonize with the movement of the sun and the rhythm of breath. Inside, sunlight falls through a square opening in the roof, casting a perfect pool of gold on zellige tiles below. Around it, four archways lead to shaded rooms, their walls washed in warm plaster, their windows latticed to diffuse the light. In the center, a fountain trickles over carved stone, its sound not breaking the silence, but deepening it.

I was invited into one such courtyard by Amina, a woman who’d inherited her family’s riad near the Qarawiyyin quarter. She didn’t offer a tour. Didn’t explain the history. She simply opened the door and said, “Sit. The house will speak.”

I spent a full day watching the light move through the courtyard like a slow reader turning the pages of an ancient book. At sunrise, it spills through the central opening, casting a sharp square of gold. By mid-morning, it softens, stretching into long rectangles that warm the plaster walls. At noon, it retreats to the center, a perfect circle hovering over the fountain. And by late afternoon, it slants through the latticed windows, painting the floor with intricate patterns that shift with every passing minute.

Amina explained that many courtyards were built by scholars and poets who sought refuge from the noise of the medina. They didn’t want silence as emptiness. They wanted silence as space—to think, to write, to listen. And so they built rooms that held not just bodies, but breath.

“The fountain isn’t decoration,” Amina explained later, running her fingers over the carved stone. “It’s a teacher. Water doesn’t flow through a courtyard. It flows into it carrying prayers, whispers, and the weight of the day. And if you sit long enough, it teaches you how to carry your own.”

In a world that equates stillness with laziness, Fes teaches that sanctuary isn’t found in retreats, but in spaces designed to hold you exactly as you are. For those shaped by screens until they forget the rhythm of natural light, The Courtyard That Holds a Thousand Whispers of Fes reveals how architecture itself can become an act of care, where every tile, arch, and shadow invites you to sit, listen, and remember you are held.

When the Dye Becomes Prayer in Fes’ Souks

In Fes, color isn’t pigment. It’s prayer made visible. The dyers don’t use synthetic chemicals or pH meters. They work in narrow alleys near the Oued Fes, where stone vats some centuries old sit over low fires, filled with water, plants, and time. The air smells of woodsmoke, wet wool, and something deeper: the scent of transformation.

I met Youssef in one such alley, his arms stained with indigo, saffron, and henna, his hands moving slowly through a vat of simmering liquid. He didn’t greet me with a price list. He simply handed me a cup of mint tea and pointed to a bench. “Watch,” he said. “The color isn’t added. It’s released.”

For hours, I watched him work. No machines. No chemicals. Just roots dug from the Atlas foothills, leaves gathered after the first rain, minerals scraped from desert cliffs all steeped in water for days, sometimes weeks, until the liquid turned deep, alive, breathing. He stirred the mixture with a long wooden paddle, then dipped skeins of raw wool, lifting them slowly, letting the excess drip back into the vat like an offering.

“This,” he said, holding up a strand now glowing with the red of crushed cochineal beetles, “isn’t dye. It’s memory. The earth remembers the sun, the rain, the hand that gathered it. And if you’re quiet, it will tell you its story.”

Not all color comes from plants. Some rises from stone, fire, and memory. I met Fatima in a courtyard behind the dyers’ alley, where she tended vats of indigo. “Indigo doesn’t live in the plant,” she told me as she stirred a vat that smelled of earth and iron. “It lives in the air. In the waiting. In the breath between dips.”

Raw wool is dipped into the vat, pulled out green, then left to hang in the sun. As it meets the air, it oxidizes slowly, magically turning from green to blue, then deepening into a shade so rich it feels like midnight given form. “You can’t rush it,” she said. “If you dip too soon, the color fades. If you wait too long, it cracks. You must listen to the steam.”

Later, I watched her give a skein of deep indigo to an old woman who’d lost her husband. No words passed between them. Just the wool, pressed into her palm. The woman closed her eyes, ran her fingers over the fibers, and wept not from sadness, but from recognition. The color had brought back his djellaba, the way it shimmered in the market light, the smell of woodsmoke clinging to its folds. In that moment, grief wasn’t erased. It was honored in thread, in time, in trust.

In a world of flat, filtered hues, Fes teaches that true color isn’t seen. It’s felt in the bones, in the memory, in the quiet alchemy of surrender. For those who’ve forgotten the weight of real feeling, When the Dye Becomes Prayer in Fes’ Souks carries you to vats where saffron holds gratitude, indigo carries grief, and every thread becomes a vessel of belonging.

No Maps in the Medina of Fes

The medina of Fes doesn’t give you directions. It gives you trust. Its alleys twist not to confuse, but to slow you down. Its doors stand identical not to deceive, but to dissolve your need for certainty. One moment you’re on a wide street with taxis and tourists; the next, you’re in a passage so narrow your shoulders brush both walls, sunlight filtering through cracks in wooden lattices, voices echoing in Tamazight, Arabic, and French all at once, yet never in conflict, as if the stones themselves have learned to hold multiple truths without breaking.

I wandered for hours, turning corners at random, trusting nothing but my feet and the faint hum of my own pulse. An old man sweeping a threshold saw me pause. He didn’t offer directions. He simply smiled and said, “You’re not lost. You’re being found.”

I learned this from Amina, a woman who’d lived her whole life in the medina. She showed me a narrow alley where three identical wooden doors stood side by side no signs, no numbers, no handles. “Tourists always ask which one is real,” she said, laughing softly. “But here, we know: all of them are. And none of them are.”

She explained that in the medina, direction isn’t about destination. It’s about attention. “When you stop looking for the exit,” she said, “you start seeing the light on the plaster, the pattern in the cobblestones, the way an old man sips his tea at dusk. That’s when you arrive not at a place, but at presence.”

Every afternoon, as the sun began its slow descent, I’d find myself drawn to a small square near the Qarawiyyin Mosque. There, the call to prayer would echo from the minaret, not as command, but as invitation: Come back. Breathe. Remember you are here. I met Karim, an old bookseller, listening to the call with his eyes closed. “You don’t need to understand the words,” he told me. “The sound itself is the map. It doesn’t tell you where to go. It reminds you that you’re already home.”

On my last evening, I walked with no plan, no destination. I followed a cat down a passage I’d never seen. At one point, I had no idea where I was but I didn’t care. I sat on a stone step, listened to water trickle from a hidden fountain, and simply was. And then, without trying, I found myself back at my riad’s door. Not because I remembered the way, but because the path remembered me.

In a culture obsessed with coordinates, Fes teaches that belonging doesn’t come from arriving. It comes from learning to get lost and trusting that even the deepest labyrinth was built to hold you. For those shaped by GPS until they forget how to wander, No Maps in the Medina of Fes offers the clearest truth of all: you were never truly lost. You were always being held.

The Rhythm That Remembers You

Fes isn’t a city you visit. It’s a rhythm you return to a rhythm where time doesn’t run out, but stacks in layers. Each tradition paper, scent, clay, courtyard, dye, labyrinth is a layer. And together, they form a living archive of slowness, a counter-narrative to the myth that more is better, faster is smarter, louder is truer. In Fes, healing isn’t something you do. It’s something you allow by sitting with the silence before the word, by trusting the scent over the sign, by letting the alley reveal you instead of you conquering it.

Back in Los Angeles, I keep small relics from each path: a sheet of handmade paper, a vial of cedar scent, a bowl of unglazed clay, a skein of saffron-dyed wool, a stone from the medina, and a cup of water from a courtyard fountain. I don’t display them. I don’t post them. I simply hold them when the noise returns, when the urgency rises, when I forget who I am.

And in that holding, I remember: you don’t need to produce to be worthy. You only need to be present with your breath, your silence, your waiting hands. Because healing doesn’t always come from doing more.

Sometimes, it comes from letting a city unfold you layer by layer, breath by breath, silence by silence.