I didn’t go to the hammam looking for wellness.

In California, I’d tried them all the infrared pods that hummed like spaceships, the cryo chambers that froze time, the two-hundred-dollar facials promising “cellular renewal” as if my skin were a failing startup. But here, on the edge of Agadir where the city dissolves into red earth and olive groves, the hammam wasn’t a destination. It was a rhythm. And it began not with booking a slot online, but with showing up on the right day usually Thursday or Sunday when the women of the neighborhood gather not to be pampered, but to belong.

I was invited by Fatima, a neighbor of Amina’s from the Souss Valley. She didn’t offer a tour. Didn’t explain the rules. She simply handed me a small bundle wrapped in faded cotton a bar of black soap she’d made herself, a lump of rhassoul clay from the Atlas mines, and a rough kessa glove woven by her mother. “Wear this,” she said. “Leave everything else outside.”

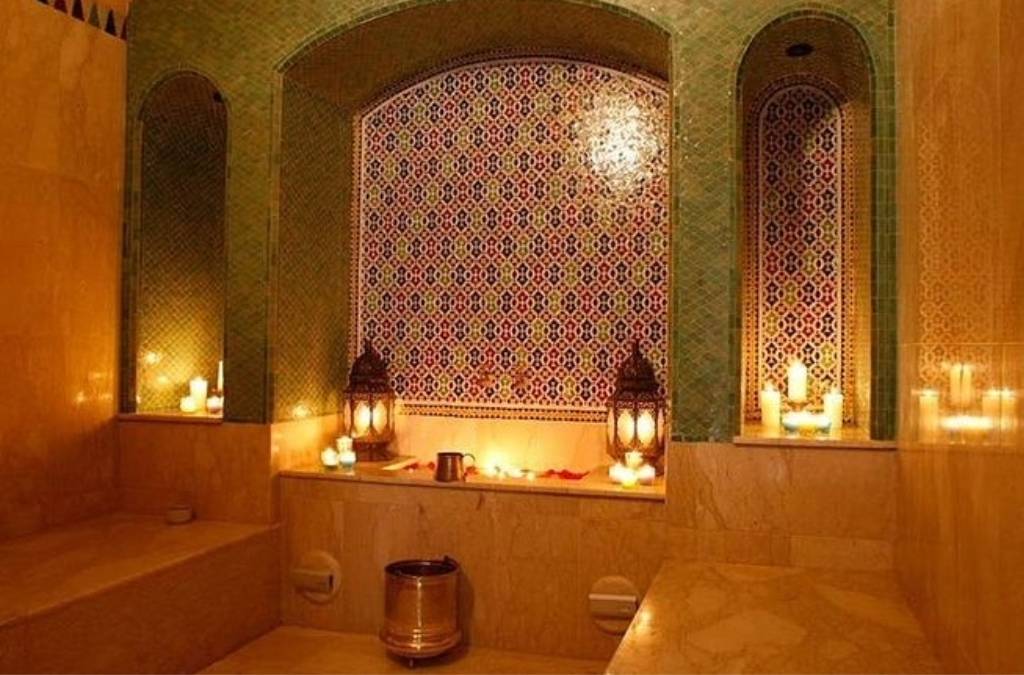

Inside, there were no robes, no slippers, no reception desk with mood lighting. Just a heavy wooden door, the scent of eucalyptus and warm stone, and the low hum of women’s voices echoing through steam like a chorus of breath. This wasn’t self-care as performance. It was care as community. And for the first time in years, I felt my body relax not because I was being treated, but because I was finally allowed to stop performing.

The Threshold of Letting Go

The entrance to the hammam wasn’t marked by a sign, but by a worn stone step and the faint sound of water dripping from copper pipes. Fatima paused before opening the door. “Here,” she said, handing me a pair of wooden sandals, “you leave your outside self behind.”

Inside the changing room, sunlight filtered through high, narrow windows, casting stripes of gold on benches lined with folded towels. Women moved quietly, undressing without shame, wrapping themselves in simple cotton sheets. No mirrors. No makeup bags. No whispered comparisons. Just bodies old, young, scarred, soft moving with the ease of those who know they are among kin.

An elder woman with silver braids handed me a cup of mint tea. “Drink,” she said. “The heat will take what you don’t need.” I sipped slowly, watching as Fatima applied black soap to her arms, massaging it in with circular motions. “This soap,” she explained, “is made from olives pressed after the first rain. We cook it for three days with eucalyptus and ash. It doesn’t clean the skin. It cleans the week.”

This was my first lesson: the hammam isn’t about beauty. It’s about release. And release begins long before you enter the steam.

The Three Rooms of Surrender

A traditional hammam near Agadir isn’t built for privacy. It’s built for presence. There are three rooms, each warmer than the last, leading to a central steam chamber where heat rises from the floor like breath from the earth itself.

The first room is for undressing not just clothes, but expectations. You leave your watch, your phone, your sense of time at the door. The air is warm but bearable, scented with dried herbs hanging from the ceiling. Women sit on low stools, pouring water over their arms, letting the day’s tension begin to loosen. No one speaks much here. Just the sound of water dripping, feet padding on tile, the occasional sigh of release.

The second room is hotter, the marble underfoot radiating warmth that climbs up your legs like a slow embrace. This is where you wait where you let your pores open, your breath deepen, your mind stop racing. Fatima sat beside me, her eyes closed, her hands resting on her knees. “Don’t fight the heat,” she whispered. “Let it find what’s hidden.”

The third room is the heart of the hammam: a dome-shaped chamber where steam coils from vents in the floor, wrapping around you like a second skin. The walls are smooth clay, the ceiling painted with faded geometric patterns that shimmer in the damp light. Here, time dissolves. And this is where the real work begins not the kind that burns calories, but the kind that releases what’s stuck grief, fatigue, the invisible weight of living in a world that never stops asking for more.

The Glove That Knows Your Skin

My turn came late morning. An elder woman with silver-streaked hair and hands like weathered stone motioned for me to lie down on the warm marble. She didn’t ask if I was ready. She just began.

The kessa glove rough, woven from natural fibers moved across my back with a pressure that bordered on pain, then melted into relief. Dead skin rolled away like old armor. My shoulders, tight for months, dropped as if they’d been waiting for this moment. She worked in silence, her movements rhythmic, unhurried, as if she’d done this a thousand times which she had, for daughters, neighbors, strangers.

When she finished one side, she tapped my hip a signal to turn. No words. Just touch as language. On my arms, she slowed, sensing tension near the elbows. On my neck, she used the edge of the glove with feather-light strokes, as if brushing away worry itself.

Later, I learned her name was Zineb. She’d been coming to this hammam since she was a girl, first with her mother, then with her daughters, now with her granddaughters. “We don’t scrub to make skin pretty,” she told me afterward, rinsing the glove in a basin. “We scrub to remind the body it’s alive.”

In California, touch is often transactional a massage booked, paid for, rated. Here, it’s relational. The hands that cleanse you belong to someone who may have lost a child, buried a husband, or carried water up this hill for fifty years. And in their touch, you feel not just exfoliation but witness.

The Clay That Holds Memory

After the scrub, Zineb motioned for me to sit. She scooped a handful of rhassoul clay from a clay bowl gray, cool, smelling of rain and deep earth and began to spread it over my arms, my back, my face. “This clay,” Fatima said from nearby, “comes from mines near the Moulouya River. Our grandmothers used it. Their grandmothers before them.”

The clay wasn’t applied for detox or glow. It was applied as grounding. As I sat wrapped in its cool embrace, the steam softened it into a second skin, drawing out not toxins, but tension. My mind, usually racing with plans and regrets, grew quiet. The only sound was the drip of water, the murmur of women speaking in low Tamazight, the soft slap of a glove on skin.

Zineb didn’t rush. She let the clay work. And in that stillness, something unexpected happened: I began to cry. Not loudly. Not dramatically. Just silent tears that mixed with the clay on my cheeks. No one looked. No one asked why. A woman nearby simply handed me a dry corner of her sheet without turning her head.

In this space, grief isn’t spoken. It’s sweated out. Held. Released. And the women around you don’t offer solutions. They simply make room for it to exist like the clay makes room for your body, like the steam makes room for your breath.

The Ritual Before the Steam

What I didn’t know when I arrived is that the hammam begins long before you cross the threshold. In many homes near Agadir, the preparation starts at dawn. Women rise early to boil water with orange blossom and rosemary. They check their bundles of soap and gloves, mend torn sheets, and sometimes bake a simple bread to share afterward.

Fatima told me that in her grandmother’s time, girls were taken to the hammam for the first time at puberty not as celebration, but as initiation into womanhood. “It wasn’t about cleanliness,” she said, stirring mint into a pot of tea the next morning. “It was about learning to be held by other women. To give care. To receive it without shame.”

Even the walk to the hammam is part of the ritual. Women go in pairs or small groups, chatting softly, carrying their bundles like sacred offerings. Children run ahead, laughing. The path itself becomes a corridor of transition from the demands of home and market, to the sanctuary of steam and stone.

This is why you can’t replicate the hammam in a luxury spa. It isn’t contained in a room. It lives in the rhythm of the week, the bond between generations, the quiet understanding that some forms of healing require no words only presence, patience, and a willingness to be seen, exactly as you are.

From Steam to Seasons

As I walked home that afternoon, wrapped in a simple cotton sheet, the city felt different. Softer. Slower. The heat on my skin wasn’t oppressive it was familiar, like the warmth of a hand on your back. I carried the scent of eucalyptus and clay with me, but more than that, I carried the quiet certainty that I’d been part of something ancient.

In this part of Morocco, the hammam isn’t separate from life it’s woven into its cycles. Women go before weddings, after childbirth, at the turn of seasons. It’s not about beauty. It’s about alignment with the body, with the community, with the rhythms of the year.

And those rhythms run deep. They’re written not in calendars, but in the stars, the harvests, the first rains. The same hands that scrub your back in the hammam also plant barley in spring, gather argan in summer, and prepare preserves before winter. Wellness here isn’t a break from life. It’s a return to its pulse.

If your spirit has been softened by the steam and stone of the hammam if you’ve learned that healing often arrives not in words, but in shared silence and strong hands then Where the Atlas Meets the Atlantic: Living Traditions Around Agadir reveals how this region’s wellness flows not from retreat, but from rhythm: in clay, steam, harvest, and the quiet strength of women who know that care is a verb. And if you’re ready to follow that rhythm into the fields and festivals, Harvesting Time: The Forgotten Rhythms of the Amazigh Calendar Around Agadir will guide you to the seasonal turns where time isn’t managed, but honored.

The Hands That Remember

The next day, Fatima took me to her aunt’s courtyard on the outskirts of Agadir, where black soap is still made the old way. In a shaded corner, three large copper cauldrons sat over low fires, bubbling with a dark paste of crushed olives, potash, and eucalyptus leaves. Her aunt, Lalla Rahma, stirred one with a long wooden paddle, her arms strong from decades of this work.

“We don’t measure,” she said when I asked about the recipe. “We feel. When the smoke smells like rain, it’s ready.”

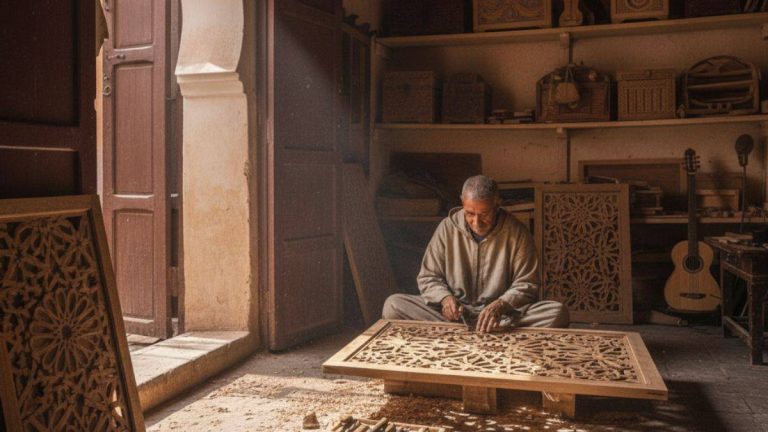

She showed me how the mixture is poured into molds, left to dry for weeks in the sun, then cut by hand. Each bar is slightly different some darker, some softer but all carry the same intention: to cleanse not just skin, but spirit.

“These hands,” she said, holding up her palms, cracked and stained with ash, “have scrubbed hundreds of women. Daughters, sisters, strangers. I don’t remember their faces. But I remember their silence. Their sighs. The way some cried without sound.”

In that moment, I understood: the hammam isn’t preserved in buildings. It’s carried in hands in the grip of the glove, the spread of the clay, the pour of warm water over tired shoulders. And as long as these hands keep moving, the tradition lives not as museum piece, but as daily act of care.

Cleanse as Continuation

Now, back in Los Angeles, I still visit spas. But I carry the hammam with me. When the steam rises, I close my eyes and remember the sound of women laughing in the next room, the weight of the clay on my skin, the way a stranger’s hands knew exactly where I held my grief.

I no longer seek wellness as escape. I seek it as return to my body, to my breath, to the quiet understanding that I don’t have to do it alone.

Sometimes, on Sunday evenings, I boil water with mint and eucalyptus, wrap myself in a plain cotton sheet, and sit in silence. No playlist. No intention setting. Just presence. And in that stillness, I feel them the women of the hammam, their hands steady, their voices low, their care unwavering.

Because some cleansing isn’t about getting clean.

It’s about remembering you belong.

And belonging, I’ve learned, is the deepest form of healing.