In Dakhla, you don’t arrive as a tourist. You arrive as a guest.

And not just of people but of the horizon itself.

I learned this on my second day in the city, when I wandered too far from the port and found myself at the edge of a dune field, disoriented by the blinding light and the sheer scale of emptiness. The Atlantic stretched to my left, the Sahara to my right, and between them, a narrow strip of life where humans had learned to dwell without dominating. A man tending goats saw me, walked over without a word, and handed me a small cup of warm camel milk. No questions. No price. Just presence. Later, I learned his name was Sidi Mohamed, and that his family had welcomed strangers this way for generations not out of duty, but because the horizon, in their view, belongs to no one. It’s a shared threshold. And anyone who crosses it is worthy of rest, food, and silence.

This isn’t hospitality as service. It’s hospitality as belonging. And in a world that turns welcome into a transaction where every smile comes with a price tag, every kindness with an expectation it feels less like generosity and more like revolution.

The Horizon Has No Borders

Dakhla sits at the end of Morocco, where the paved road dissolves into sand and the desert meets the sea in a long, curving embrace. But culturally, it’s not an end it’s a beginning. A gateway where Africa pours in from the south and east, carrying stories, spices, rhythms, and resilience. Walk through the Friday market, and you’ll hear Hassani Arabic blending with Wolof, Pulaar, Soninke, and French not as competition, but as conversation. Men from Nouakchott trade dried octopus for handwoven belts. Women from Bamako sell indigo-dyed cloth next to locals offering salt-cured sardines and argan oil pressed from nuts gathered near the Mauritanian border. No one asks for papers before sharing tea. No one measures your worth by your passport.

“The horizon doesn’t carry a passport,” Sidi Mohamed told me one evening as we sat outside his tent, watching the sun sink into the Atlantic in a blaze of orange and violet. “Why should we?”

This openness isn’t naivety. It’s hard-won wisdom. For centuries, the Sahara has been a corridor, not a barrier. Caravans laden with salt and gold, fishermen following fish stocks, poets fleeing drought, refugees escaping conflict all have passed through Dakhla, leaving traces of rhythm, recipe, and ritual. And instead of building walls to keep the world out, the people here built courtyards with open sides, low walls, and always an extra mat rolled in the corner, waiting.

To be a guest here is to be reminded of something ancient: you belong simply because you’ve arrived. Not because you’ve earned it, paid for it, or proven yourself. But because existence itself is enough.

Tea That Asks No Questions

The ritual begins not with words, but with water.

In Sidi Mohamed’s courtyard, the kettle is always on. When a stranger appears whether from Lisbon, Dakar, Timbuktu, or even Los Angeles the first gesture is never inquiry. It’s invitation. “Sit,” he says, placing a small glass before you. “The tea is ready.”

Three pours follow, as in much of Morocco, but here, the silence between them holds more weight than the liquid itself. No one asks where you’re from, what you do, how long you’ll stay, or whether you can afford to pay. Those questions come later if at all. First, there is only shared breath, the scent of fresh mint crushed by hand, and the slow unfurling of presence that happens when you’re not being sized up.

I once sat beside a young man from Conakry who hadn’t spoken in two days. He’d crossed the desert alone, his shoes worn to threads, his eyes hollow with exhaustion. Sidi Mohamed poured him tea, offered flatbread with olive oil, and said nothing for nearly an hour. Only when the third glass was empty did the young man speak, his voice barely a whisper: “You didn’t ask if I had money.” Sidi Mohamed smiled gently. “The horizon doesn’t charge tolls. Why would I?”

In this economy of care, worth isn’t earned. It’s assumed. And that assumption that every human being deserves dignity before explanation, shelter before scrutiny is the quietest, most radical form of healing I’ve ever witnessed.

For those who’ve grown weary of being sized up before being welcomed, who’ve felt the sting of conditional kindness, Dakhla’s Pulse: Traditions Where the Sahara Greets the Atlantic reveals how an entire region lives by a different covenant: one where belonging precedes identity, and grace flows without invoice, expectation, or expiration date.

The Courtyard That Holds Everyone

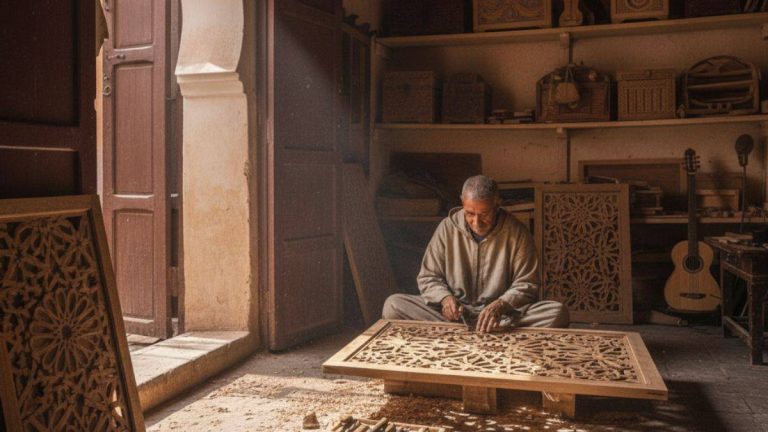

Sidi Mohamed’s courtyard wasn’t grand. Just packed earth swept clean each morning, a few low stools carved from driftwood, and a tamarisk tree offering thin but precious shade. But it held more than people it held stories, songs, and silences that needed no translation. A Senegalese musician tuning his xalam in the corner, fingers coaxing melodies older than borders. A Mauritanian trader mending a leather satchel with sinew and patience. A French photographer who’d lost her way, now laughing over dates with a local fisherman’s wife, their hands moving in the same rhythm as they shelled almonds.

No one was introduced by title, nationality, or profession. They were simply here and that was enough. Identity wasn’t a credential. Presence was.

“What fills a space isn’t walls,” Sidi Mohamed said one afternoon, watching children from three different countries chase a ball made of rags. “It’s willingness. Willingness to share shade. To listen. To let someone else’s story live beside yours without crowding it.”

His courtyard had no gate. No fence. Just an open side facing the dunes, as if to say: Come. Stay. You’re already part of this.

I asked him once how he decides who to welcome. He looked at me like I’d asked why the sea is wet. “The horizon sends them,” he said. “Who am I to refuse what the wind brings? My grandfather welcomed a Portuguese sailor in 1947. My father gave shelter to a Malian teacher during the drought of 1984. Now it’s my turn. One day, it will be my son’s. This isn’t charity. It’s continuity.”

This isn’t idealism. It’s ecology. In the desert, isolation is death. Connection is survival. And over centuries, that necessity has ripened into generosity not as a moral virtue, but as a daily rhythm. You share water because you’ve been thirsty. You offer bread because you’ve known hunger. You make space because you’ve been lost.

In Dakhla, hospitality isn’t a virtue you admire from afar. It’s a verb you practice every day not in grand gestures, but in small, steady acts that stitch strangers into the fabric of community, one cup of tea at a time.

When the Stranger Becomes Kin

I stayed with Sidi Mohamed for three nights. By the second evening, I was no longer “the American writer.” I was just “Even,” the one who liked his tea strong, asked too many questions, and couldn’t tie a proper knot. His daughter, Leila, brought me a scarf she’d woven blue with white dots, like stars over the bay. “For the wind,” she said, draping it around my shoulders. His son, Youssef, showed me how to read the tide by the color of the foam green for calm, silver for fish, gray for storms. No one treated me as a guest to be served or a story to be extracted. I was becoming part of the rhythm.

This is the alchemy of Dakhla’s hospitality: it doesn’t keep you at arm’s length with polite distance. It draws you in not to convert you, impress you, or sell you something, but to remind you that you were never truly separate. The stranger isn’t other. They’re simply someone the horizon hasn’t introduced yet.

One afternoon, a woman from Mali arrived, exhausted, her child asleep on her back, her clothes dusty from weeks of travel. Without ceremony, Sidi Mohamed’s wife, Fatima, laid out a mat in the coolest corner, heated broth with ginger and mint, and began braiding the girl’s hair with gentle, practiced hands. No paperwork. No interrogation. Just hands that knew how to hold what was offered without demanding explanation.

Later, the woman joined us for tea. She didn’t speak Hassani, but she hummed a lullaby from her village a melody that blended with the wind through the tamarisk leaves and the distant crash of waves. In that moment, language wasn’t needed. Belonging was already spoken in the space between notes, in the shared silence, in the way Fatima refilled her glass without being asked.

If your spirit has been worn thin by a world that demands proof of worth before offering kindness if you’ve ever felt like a visitor in your own life then Drums That Know the Tide will carry you deeper into Dakhla’s living pulse where rhythm, not words, heals the rift between self and other, and where every heartbeat echoes the sea’s ancient song of return.

The Gift That Returns to You

On my last morning, I tried to leave money for Sidi Mohamed. He refused, gently but firmly, placing his hand over mine. “You think you received a gift?” he said, his eyes kind but insistent. “No. You gave one. Your presence reminded us that the horizon still sends good people. That the world hasn’t forgotten how to walk with humility.”

I walked away confused until weeks later, back in Los Angeles, I found myself inviting a homeless man to share my coffee without asking his story, without checking if he “deserved” it. It happened without thought. Like breathing. Like pouring tea.

That’s the secret of Dakhla’s hospitality: it doesn’t just feed the guest. It renews the host. In welcoming the unknown, you remember your own humanity. You remember that you, too, have been lost. That you, too, have needed shelter. And in that remembering, you heal not by fixing yourself, but by reconnecting to the simple, radical truth that we are all guests of the same vast, generous sky.