I never thought a tree could teach me patience.

But then, I’d never stood beneath an argan tree in the early morning light, watching a woman’s hands move like they’d memorized every groove in the nut, every whisper of the stone beneath it. There’s a rhythm here that doesn’t belong to clocks or calendars. It belongs to the land, to generations of women who’ve turned bitterness into gold not for export, not for Instagram, but because their bodies and their children needed it to survive.

Most of what the world knows about argan oil comes in sleek glass bottles, labeled “organic,” “cold-pressed,” or “Moroccan miracle.” And sure, it’s miraculous but not in the way marketing makes it seem. The real miracle isn’t in the oil itself. It’s in the hands that make it, the forest that shelters it, and the quiet refusal of these women to let their knowledge become just another commodity.

When I left the noisy version of wellness behind in California and arrived in Essaouira, I didn’t come looking for skincare. I came looking for stillness. But stillness, I learned, often arrives through the most ordinary acts: grinding seeds, stirring paste, sharing bread under a tree that’s older than your grandparents. And in that stillness, I finally understood why argan oil here isn’t just something you put on your face. It’s something you carry in your bones.

The Argan Forest: A Living Archive of Resilience

Thirty kilometers inland from Essaouira, the landscape changes. The ocean breeze softens, the sky widens, and suddenly you’re driving through a sea of gnarled, twisted trees that look like they’ve been arguing with the wind for centuries. This is the argan forest a UNESCO-protected biosphere that stretches across southwestern Morocco, one of the last places on Earth where these trees grow wild.

The argan tree isn’t beautiful in the conventional sense. Its bark is rough, its branches crooked, its leaves small and stubborn. It thrives in semi-arid conditions where few other plants survive, its deep roots gripping the earth like fingers refusing to let go. Locals say the tree can live for 200 years. Some say 400. No one knows for sure because no one has ever tried to cut one down just to count its rings. That would be like cutting open your grandmother to see how old she is.

What’s remarkable isn’t just the tree’s endurance, but what it gives while enduring. Twice a year, its fruit ripens small, round, and green, with a fleshy exterior that dries and falls away, leaving behind a hard nut. Inside that nut: one to three kernels. And from those kernels, after hours of cracking, grinding, and pressing, comes the oil.

But here’s what most outsiders miss: the forest isn’t just a source of raw material. It’s a social space, a pharmacy, a classroom. Goatherds lead their flocks through its shade. Children collect fallen fruit after rain. Women gather under its canopy to talk, laugh, and work. The tree doesn’t just feed the body it holds the community together.

And yet, this forest is fragile. Climate change, overgrazing, and urban expansion have thinned its borders. That’s why, in the 1990s, a quiet revolution began not with protests, but with cooperatives. Women, many of them widowed or divorced, banded together to protect both the tree and their dignity. They formed collectives that processed oil not for middlemen, but for themselves. They registered trademarks, trained younger women, and slowly reclaimed the narrative. Argan oil wasn’t just a beauty product. It was a lifeline.

Why the Forest Can’t Be Replicated

You can grow argan trees in labs. You can extract oil with machines. But you can’t replicate the ecosystem that makes this oil what it is. The soil here is rich in minerals washed down from the Atlas Mountains. The climate hot days, cool nights, salty air from the Atlantic stresses the tree just enough to deepen the oil’s antioxidant properties. Science can analyze the composition, but it can’t reproduce the memory stored in the land.

One afternoon, I sat with Amina, a cooperative leader near Diabat, as she stirred a clay pot of roasted argan paste. “People think the oil is made in the mill,” she said, her eyes never leaving her work. “But it’s made in the forest. The tree decides the taste. The rain decides the color. We just listen.”

That’s the first lesson of argan oil: you don’t control it. You receive it.

Hands That Turn Bitterness into Gold

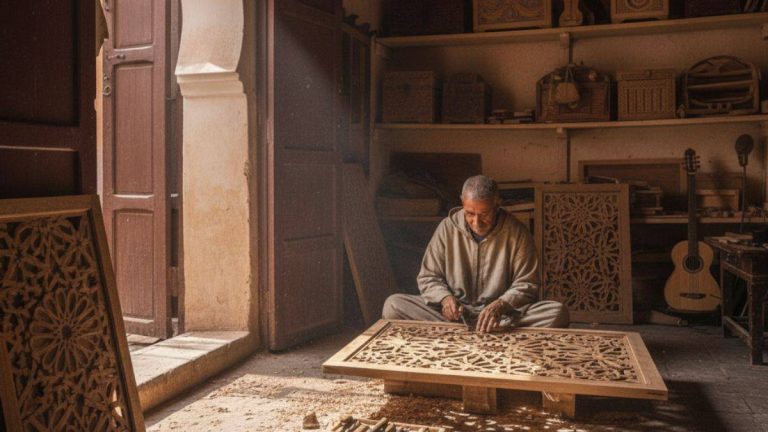

The first time I watched argan nuts being cracked, I thought it was a performance.

The women sat on low stools in a sun-drenched courtyard, their hands moving with a speed that seemed impossible. Each held a smooth stone in her palm the same kind of stone you’d skip across the ocean back in California and with a sharp tap, the hard shell split open, revealing the pale kernel inside. No gloves. No safety goggles. Just decades of muscle memory and a kind of quiet focus that made the whole scene feel sacred.

I asked Leila, the woman who ran the riad in Essaouira, why they didn’t use machines. “Machines don’t know when a nut is ripe,” she said simply. “Hands do.”

That’s the heart of it, isn’t it? In a world obsessed with efficiency, these women choose slowness not because they have to, but because they’ve learned that some things lose their soul when rushed. The bitterness of the raw kernel, for instance, must be roasted just enough to mellow, not masked. The grinding must be slow enough to release the oil without burning it. And the pressing still done with stone mills turned by hand in many cooperatives requires a rhythm that matches the breath, not the clock.

The Cooperative Model: More Than Economics

When outsiders hear “argan cooperative,” they often picture a small business. But it’s far more than that. For many women in rural Morocco, joining a cooperative is their first step toward financial independence, literacy, and even legal rights. Before the 1990s, most of these women had never held a bank account. Today, they manage budgets, negotiate exports, and teach apprentices as young as fifteen.

But what struck me most wasn’t the economics it was the atmosphere. There was no boss. No performance reviews. Just a shared understanding: we feed each other. While they worked, they passed around tea. They sang old Amazigh songs. They watched each other’s children nap in the shade. When Fatima’s daughter fell and scraped her knee, three women dropped their stones at once to tend to her. No one asked who was “on break.” They just moved as one body.

This is the second lesson of argan oil: wellness isn’t individual. It’s woven into how we care for each other while we work.

I tried my hand at cracking nuts once. Within minutes, my palms ached, my rhythm was off, and I’d shattered more kernels than I’d saved. Fatima laughed not unkindly and placed her hand over mine. “Don’t fight the nut,” she said. “Let the stone meet it where it’s ready to open.”

It sounded like advice for life.

From Kitchen Remedy to Global Symbol And Back Again

By the early 2000s, argan oil had gone global. Beauty brands in Paris, New York, and Los Angeles began bottling it as “liquid gold,” touting its anti-aging properties and rare fatty acids. Demand exploded. Prices soared. Suddenly, a product that had been traded in clay jars at local souks was selling for fifty dollars an ounce in Sephora.

For a while, this seemed like a win. Cooperatives saw more income. International NGOs poured funding into “women’s empowerment” projects. Tourists flocked to Essaouira asking for “authentic argan experiences.”

But something shifted. The focus moved from oil as nourishment to oil as luxury. Machine-pressed versions faster, cheaper, less flavorful began flooding the market, often mislabeled as “handmade.” Some big brands even started sourcing kernels from wild goats that climb argan trees (yes, really) a spectacle that drew crowds but degraded the forest and bypassed the women entirely.

The women noticed. And they pushed back.

Many cooperatives stopped selling raw oil to middlemen. Instead, they began bottling their own small batches, with clear labeling, often in partnership with ethical importers. They invited visitors not to “watch a demo,” but to sit, share tea, and learn why this oil is eaten as often as it’s applied. Because here, argan oil isn’t just for glowing skin it’s for strong bones, healthy digestion, and resilience during illness.

One elderly woman, Zahra, told me she gives a spoonful to every child in her family each morning, mixed with honey and almonds. “It’s not medicine,” she said. “It’s protection.”

Eating the Oil: A Forgotten Tradition

Back home in California, I’d only ever used argan oil topically. But in Essaouira, I tasted it raw earthy, slightly nutty, with a finish that lingered like good olive oil. Leila drizzled it over roasted vegetables. A fisherman’s wife stirred it into couscous. At the cooperative, they served it with warm bread and olives for breakfast.

Nutritionally, culinary argan oil is roasted before pressing, which deepens its flavor and boosts certain antioxidants. It’s rich in vitamin E, essential fatty acids, and squalene compounds that support heart health, reduce inflammation, and protect cells from oxidative stress. But locals don’t talk about “squalene.” They talk about how it warms you in winter. How it helps a nursing mother’s milk flow. How it steadies the nerves.

This brings us to the third lesson: the line between food, medicine, and ritual is invisible here and maybe it should be everywhere.

If you’ve sensed that thread running through Essaouira’s approach to living well the ocean as companion, the hammam as weekly reset, the rhythm of the tide as guide you’ve already glimpsed the foundation of a deeper truth. Wellness and Cultural Travel in Essaouira: The Ocean, The Body, and The Quiet Mind explores how these elements form a coherent, centuries-old philosophy of care that needs no branding to be valid.

The Ritual of Application: More Than Skin Deep

In Essaouira, you don’t just apply argan oil you anoint.

There’s a quiet ceremony to it, even when no one’s watching. A woman might warm a few drops between her palms before pressing them into her child’s hair after a bath. An elder might massage it into her temples at sunset, not to “reduce wrinkles,” but to soothe the day’s weight from her brow. I watched Leila rub it into her hands each night before bed, not as skincare, but as a kind of closing prayer for her body.

This ritual isn’t about aesthetics. It’s about acknowledgment of tired skin, of shared vulnerability, of the simple truth that touch matters. When Fatima massaged oil into my hands that first afternoon at the cooperative, her touch wasn’t clinical. It was maternal. She didn’t ask about my skin type. She asked if I’d been sleeping.

That’s the quiet rebellion of this tradition: it refuses to separate care from connection.

Massage, Memory, and the Language of Touch

Traditional argan oil massage in this region often blends with practices passed down through Amazigh (Berber) lineages. There are no set routines, no “ten-minute facial protocols.” Instead, the giver reads the receiver’s body the tension in the shoulders, the dryness of the elbows, the way someone holds their breath and responds.

I received one such massage from Amina, the same woman who led the hammam session I wrote about earlier. She used warm argan oil infused with wild rosemary gathered near the Oued Ksob river. As her hands moved, she hummed an old lullaby soft, wordless. No explanations. No upsells. Just presence.

Afterward, I asked her what the song meant. She smiled. “It’s not about the words. It’s about the vibration. The oil carries it into your bones.”

Science might call this placebo. But in Essaouira, they call it transmission of care, of history, of resilience. The oil becomes a vessel, and the hands, the voice, the silence around them, become the ritual.

This is where global wellness often misses the mark. It extracts the oil but discards the context. It sells the glow but forgets the grief, the labor, the laughter that gave the oil its depth. Here, you can’t have one without the other.

Choosing Oil That Honors Its Roots

Not all argan oil is created equal and not all of it honors the hands that made it.

If you’re drawn to bring a piece of this tradition home (as I was), the way you choose matters more than the price tag. True, ethical argan oil doesn’t come with flashy packaging or celebrity endorsements. It often arrives in simple amber glass or tin, labeled with the cooperative’s name, not a brand.

Look for these signs: “cooperative-made” or “women’s cooperative” on the label, “roasted” for culinary or “unroasted” for cosmetic clearly specified, “cold-pressed and hand-extracted” not solvent-extracted, and Fair Trade or direct-trade certification, or better yet, a transparent story of origin.

Avoid anything labeled “goat-collected” unless you’ve verified it supports forest conservation and compensates women fairly most don’t. And be wary of prices that seem too good to be true. Real hand-pressed argan oil takes roughly thirty kilograms of argan fruit and fifteen to twenty hours of labor to produce one liter. If it’s cheap, someone’s labor has been erased.

During my last week in Essaouira, I bought a small bottle from Fatima’s cooperative. She filled it herself, sealed it with wax, and tied a strip of indigo-dyed cloth around the neck. “For when you forget how to slow down,” she said.

I keep it on my windowsill in California. I don’t use it every day. But when I do, I warm it in my palms, close my eyes, and remember: wellness isn’t something you consume. It’s something you return to like a forest, like a rhythm, like a woman’s hands that know exactly where you’re holding your grief.

Carrying the Tradition Forward Without Carrying It Away

Leaving Essaouira, I realized I didn’t need to “bring wellness home.”

It was already here in the way I walked, the way I listened, the permission I’d learned to give myself to do less. The argan oil was just a reminder, a tactile thread connecting me back to that truth.

And that’s the final lesson: sacred traditions aren’t meant to be exported they’re meant to be experienced, honored, and then released.

You don’t need to own the oil to carry its wisdom. You just need to remember that healing can be slow, communal, and deeply ordinary.

If this story has stirred something in you if you find yourself wondering about the women who keep other ancient traditions alive across Morocco, from saffron harvests in Taliouine to henna ceremonies in the Atlas foothills then Gnaoua Music Therapy and Spiritual Trance will take you deeper into those quiet, resilient worlds where culture isn’t performed for tourists, but lived with dignity, day after day.